An ichthyosaur fossil of the Jurassic period, Dinosaurland Fossil Museum, Lyme Regis, Dorset, England

© Christopher Jones/Alam

Celebrating a young girl's age-old discovery

When 12-year-old Mary Anning uncovered the complete skeleton of a fish-like creature near her home on England's southern coast in 1811, extinction was a shaky idea in science. Fossils were nothing new—everything dies and leaves remains, after all. But could an entire species really die off? Were more of these five metres sea monsters lurking in the depths of the English Channel?

The fact that ichthyosaurs like this went extinct 90 million years ago seems obvious. But though such definite answers were still only suspicions during Mary Anning's lifetime, she persisted with paleontology. Her prolific fossil finds fuelled both public interest and scientific understanding, and she even discovered two more species in her 20s: the pterodactyl and the plesiosaur. Though she died young at 47, largely denied recognition as a woman in Victorian society, her influence endures like the fossils that fascinated her.

Related Images

Bing Today Images

Sea turtle, Fernando de Noronha, Brazil

Sea turtle, Fernando de Noronha, Brazil

Steller sea lions, Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Steller sea lions, Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Atlantic spotted dolphins near Santa Maria Island, Azores, Portugal

Atlantic spotted dolphins near Santa Maria Island, Azores, Portugal

Group of giant cuttlefish in Spencer Gulf, off Whyalla, South Australia

Group of giant cuttlefish in Spencer Gulf, off Whyalla, South Australia

Humpback whale mother and calf, Tonga

Humpback whale mother and calf, Tonga

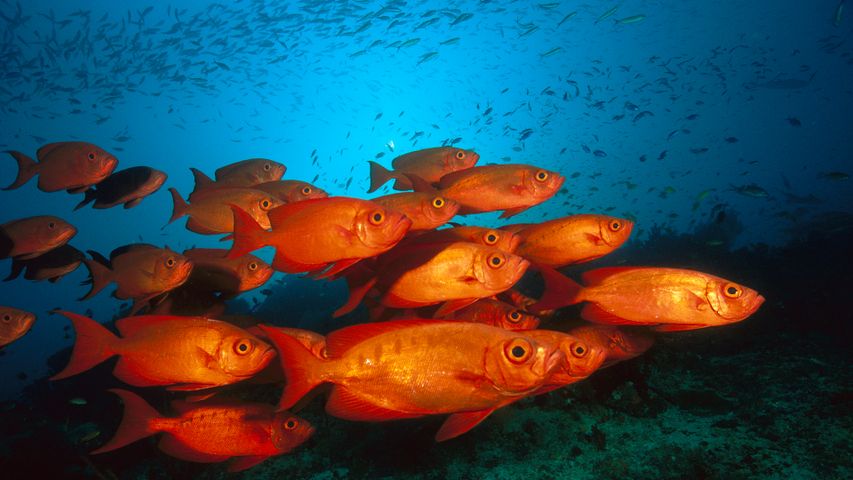

Crescent-tail bigeye fish in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia

Crescent-tail bigeye fish in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia

A green sea turtle swims in the Pacific Ocean near the French overseas territory of New Caledonia

A green sea turtle swims in the Pacific Ocean near the French overseas territory of New Caledonia

California sea lion in a forest of giant kelp, Baja California, Mexico

California sea lion in a forest of giant kelp, Baja California, Mexico